Seychelles has one of the world’s highest rate of stranded dFADs

A recent global study on drifting Fish Aggregating Devices (dFADs) (The global footprint of drifting fish aggregating devices | Science Advances) has uncovered a concerning truth: Seychelles is one of the hardest-hit areas on the planet by dFADs, which have serious implications for its delicate marine ecosystems.

dFADs are floating devices that industrial tuna fleets use to lure fish. While they catch fish, they also drift for hundreds or even thousands of kilometres, eventually washing up on coastlines and coral reefs. Constructed from synthetic materials and nets, they pose a threat to marine habitats, pollute oceans, and can entangle wildlife.

According to the paper, from 2007 to 2021, the world’s tuna fleets deployed around 1.41 million dFADs, covering at least 134 million square kilometres, roughly 37% of the Earth’s oceans (Escalle et al., 2025). These devices have ended up stranded in 104 maritime jurisdictions worldwide.

The highest numbers of strandings were reported in Seychelles, Somalia, and French Polynesia, which together account for 43% of all recorded incidents (Escalle et al., 2025).

The study highlights that Seychelles has one of the highest concentrations of dFAD strandings globally. Alarmingly, over a third of these beachings occur on coral habitats, which are vital ecosystems that are already under pressure from climate change.

The impacts include:

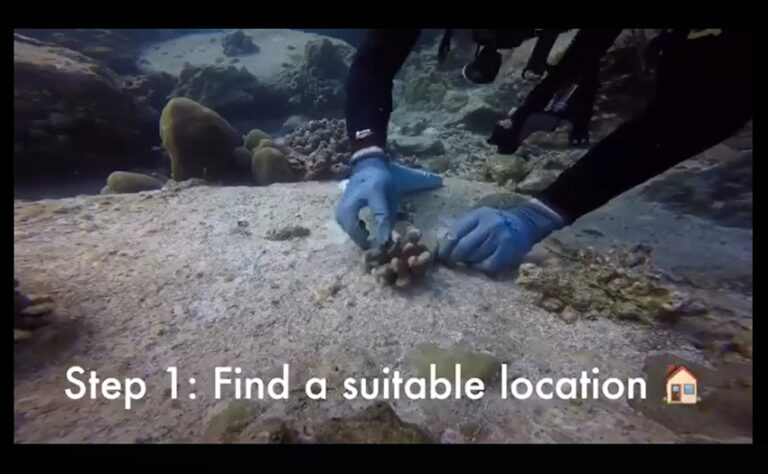

- Coral reef damage: Physical harm caused by heavy structures and nets.

- Marine pollution: Plastics and fishing debris littering the coastlines.

- Economic costs: Cleanup and reef restoration often fall on local communities and government agencies.

Most dFADs found in Seychelles originate from industrial purse seine fleets operating far from its shores. The study points out that existing governance frameworks make it challenging to trace these devices back to their owners, leaving coastal states like Seychelles to cope with the environmental and economic repercussions (Escalle et al., 2025).

Experts and environmental groups are urging for stricter accountability laws to ensure that vessel owners take responsibility for lost dFADs; enhanced monitoring through regional registries, like the Indian Ocean Tuna Commission’s upcoming dFAD registry, which is set to launch in 2026; caps on the number of dFADs and mandates for biodegradable, non-entangling designs; and focused removal programs in areas with delicate ecosystems, such as coral reefs.

The study shines a light on the western Indian Ocean, identifying it as a key fishing area where these devices are widely utilized. What’s concerning is that the tuna stocks in the Indian Ocean are already facing significant strain, with around 40% of the catch coming from overfished yellowfin and bigeye populations.

Additionally, the paper pointed out a serious gap in data for our region. The authors discovered that a large part of the missing information regarding dFAD deployments in the Indian Ocean was “almost entirely due to the lack of reports from Seychelles-flagged vessels.” This absence of thorough reporting complicates our ability to grasp and tackle the full scope of the dFAD problem, making it even tougher to safeguard Seychelles’ precious marine ecosystems.

Source: Escalle, L., et al. (2025). The global footprint of drifting fish aggregating devices. Science Advances, 11(19), eads2902. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.ads2902